In the Middle of My Own Storm

Here’s a question for you: Do you know the Joker who juggles 3 balls in his hands? Have…

August 8, 2018

[dropcaps type=’square’ font_size=’80’ color=’#4a4a4a’ background_color=’#ffffff’ border_color=”]T[/dropcaps]hey say, the best start-up founders “solve the problems that hurt them the most”. So, I’m finally doing it. I’m making an attempt to solve a problem that hurt me the most – the way the higher education system works in India. Allow me to explain.

I did a degree in Engineering from one of the well-known colleges in Pune. I chose to do Mechanical engineering, although I was in love with programming and computers. My father was a Mechanical engineer. I had this crazy notion that mechanical engineering is the ‘mother’ of all engineering and that after studying that, one can pursue any field one chooses. I chose to do mechanical although programming was my talent and my passion.

There was no-one or no process to guide me with what I should have done, what I would have been good at, and how I should have taken decisions about my career.

When I started college, I was super excited about ‘becoming an engineer’. I wanted to learn new things, make stuff, experiment with mechanics, and get my hands dirty in the workshop. But the first year of engineering is a bunch of theoretical subjects with funny acronyms like (TOM, SOM, and M2) that everyone has to study. There is no choice. It is a total ‘killjoy’. I realised, very quickly, that engineering college was really nothing but a bigger school, with fatter textbooks, more students per class, and a lot more cramming.

The first year of engineering systematically destroyed whatever little remnants of curiosity I had left in me. The excitement of becoming an engineer had dulled.

Somehow, I made it to the second year with only two ATKT’s (I know it sounds like the name of a machine gun, but ATKT means ‘allowed to keep terms’, which is a sophisticated way of saying I failed in a subject)! I thought that finally, I will get to do some ‘real engineering’. But soon I realised that what was called as ‘practicals’ was nothing but performing standardised procedures in the laboratory. It was mostly about writing pages and pages of journals, which was usually handed down as a legacy from the seniors. We just had to copy it.

[blockquote text=” There was nothing practical about what were called as ‘practicals’. There were no ‘real’ problems to solve or projects to work on.” text_color=”” width=”” line_height=”undefined” background_color=”” border_color=”” show_quote_icon=”yes” quote_icon_color=”#4285F4″]

I was a very enthusiastic character, as I am even now. I wanted to get my hands on some real-life projects. I enjoyed business as much as technology. Eventually, I found a project of my own. I designed an electronic metronome that was used by students of music. I found a radio repair shop on MG Road and convinced the owner to teach me how to solder. I used to share my lunch dabba with him. Eventually, I succeeded. What existed in the market, cost Rs.3000 and what I had made, cost Rs.500 including my profit. Over a year, I made and sold more that 50 such metronomes! I had a little factory running at my house, with my cook and the watchman, who I had trained to build electronic circuits! But all this was on my own individual initiative. No teacher, no one at college knew or supported my little venture.

There were no business or management courses, in spite of the fact that today most of my batchmates are engineers who either have their own business or work in a business function for a company.

Without even realising it, and not really by choice, I slipped into the mode of ‘bunking’ lectures every now and then. College became more of a hang-out. There was a lot of free time. Exams usually required only the last few weeks of cramming, and I was smart enough to know how to study so as to get decent marks. Most of college life was spent hanging out and making bike trips to Lonavala for a ‘quick coffee’. (don’t get me wrong, those trip taught me a lot about life, and got me some of my best friends!)

There was too much idle time. When the mind wasn’t engaged in exciting projects, it found other exciting things to do, which weren’t related to engineering, business or anything even close!

As the final years approached, the realisation hit us that we need to start thinking about what to do next. A mad rush took hold. Some (almost 50%) had decided to go abroad for a Masters. Some applied to IT companies (those were the years of the IT rush). But no one knew what exactly to do, how to decide what kind of company or work to choose, or how to negotiate our salary and job, or even the importance of finding the right first boss. We were left to our own means and devices, and to the counsel of our friends and family (although I doubt how much family is really in a position to guide us on this topic).

[blockquote text=”There was no process to help us transition from the cozy comfort of engineering college to the harsh reality of the world beyond. No process existed for self-analysis, career-discovery, or exposure to industry practitioners.” text_color=”” width=”” line_height=”undefined” background_color=”” border_color=”” show_quote_icon=”yes” quote_icon_color=”#4285F4″]

Please, don’t get me wrong. I’m not being a pessimist. There were also many fabulous things that happened to me during my engineering years. I made some great friends, met a few wonderful teachers, learned some fascinating things, and discovered the ways of the world. I’m just saying that I feel much more could have been done to keep our young minds engaged.

Also, I attach a disclaimer here that at the end of the day it is the choice of the individual. I have some good friends who were super disciplined and stayed on course for the entire four years. So, I am not blaming the system. I take the blame on myself.

Yet, the point remains is that I found myself being hurt in this process. I wanted to do much more. If I had had a platform which had given me even a little encouragement and support, I would have jumped at it. I am sure of that.

In the last few years, I have had intense conversations with many of my students and their parents. I realise that, largely, the problem still exists.

Based on my own experience, here is what believe I should have done, or every ‘business-minded’ engineering student should aim to do:

The truth is that over a period of time, I did all of these things. And I owe gratitude to my parents, my mentors and my education. It is these stories of failed and successful projects that have truly made me who I am. What would have been absolutely amazing, is if I had been able to have access to these experiences while at college. Some universities abroad, and even in India, do provide such environments. Some families are able to create this for there young. I believe such exposure could have catalysed and accelerated my journey of self-discovery towards working for a ‘life’, rather than just working for a ‘living’.

I owe tremendous gratitude to my engineering years. It was an intense and fascinating journey. Every journey has its share of problems. Problems are nothing but an opportunity to find solutions. We love finding solutions. Hence, we see problems as beautiful gifts!

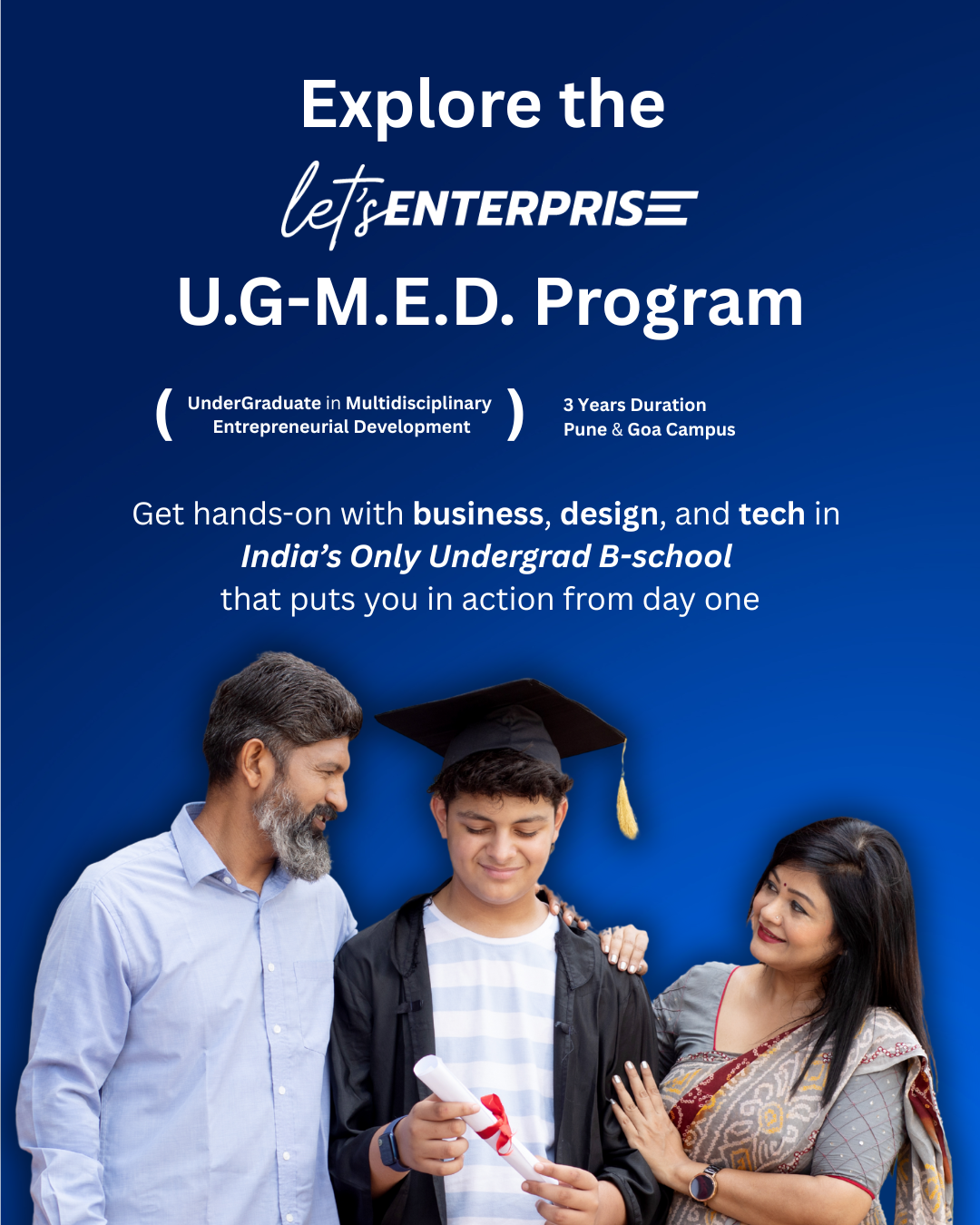

Let's Enterprise is a pioneering educational institution that empowers students with hands-on business skills through its unique UG-M.E.D. program. With campuses in Pune and Goa, it bridges the gap between traditional learning and real-world experience, shaping the future of tomorrow's entrepreneurs.

Discover how our first-year students are actively engaging in real-world business projects, guided by facilitator Sharjeel Shaikh.